Understanding the quick first shell tool in Artemis

ARTEMIS offers several ways to get information from FEFF into a

fitting model. One of these is called a quick

first shell path. It's purpose is to provide a model-free

way of computing the scattering amplitude and phase shift well enough

to be used for a quick analysis of the first coordination shell.

The way it works is quite simple. Given the species of the absorber

and the scatterer, the absorption edge (usually K or LIII), and a

nominal distance between the absorber and the scatterer, ARTEMIS

constructs input for FEFF. This input data assumes that the absorber

and scatterer are present in a rock salt structured crystal. The lattice constant of this

notional cubic crystal is such that the nearest neighbor distance is

the nominal distance supplied by the user. FEFF is run and the

scattering path for the nearest neighbor is retained. The rest of the

FEFF calculation is discarded. The nearest neighbor path is imported

into ARTEMIS with the degeneracy set to 1.

The assumption here is that the notional crystal will produce a

scattering amplitude and phase shift for the nearest neighbor path

that is close enough to what would be calculated by FEFF were the

local structure actually known. Does this really work?

Using the quick first shell tool to model first shell data

To demonstrate what QFS does and to explain the constraints on the

situations in which it can be expected to work, let's take a

look at my favorite teaching example, FeS2. Anyone who has attended

one of my XAS training courses has seen this example.

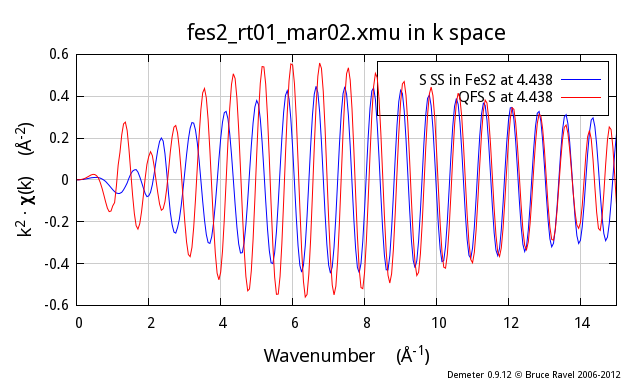

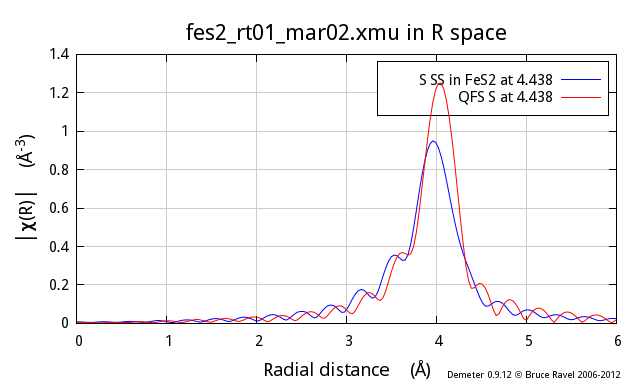

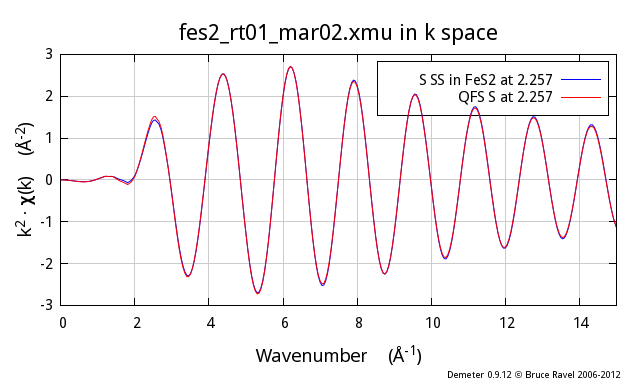

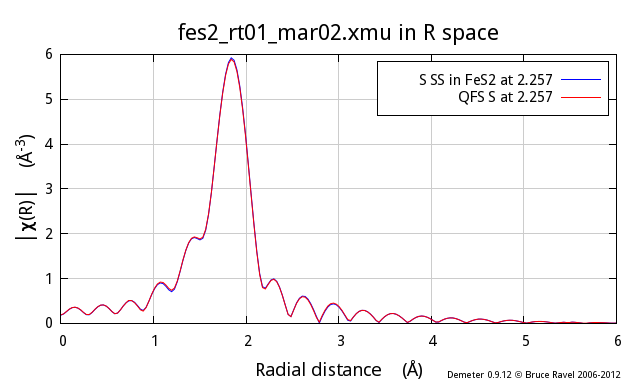

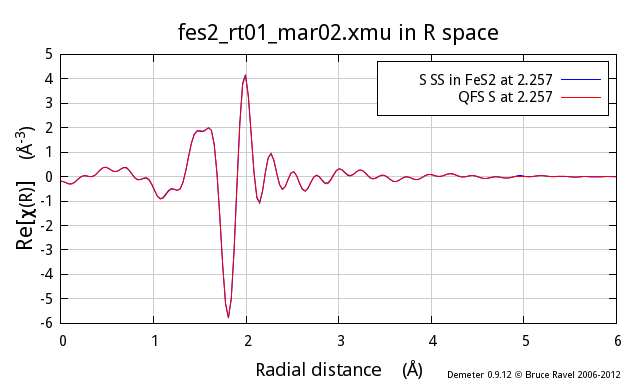

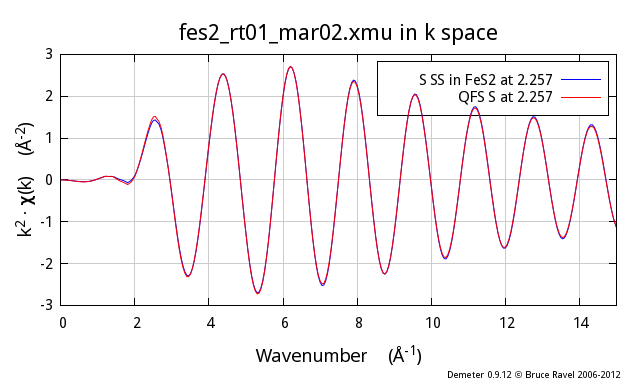

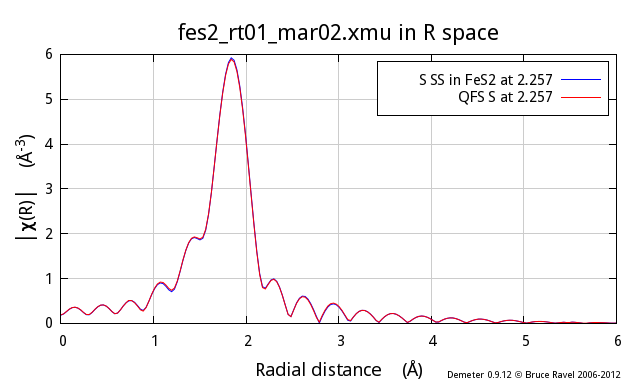

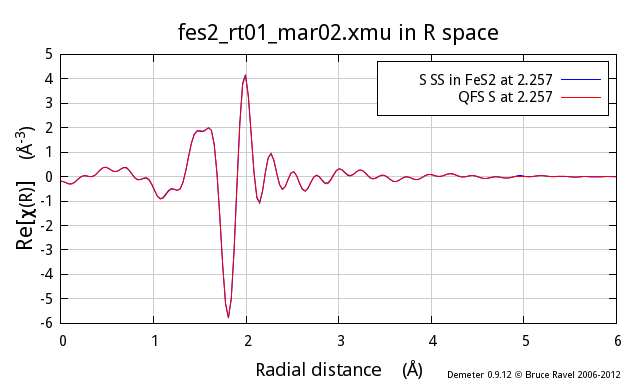

These three figures show the S atom in the 1st coordination shell

computed using the known crystal structure for FeS2. This

calculation is the blue trace. The red trace is the contribution from

a S atom at the same distance as computed using the quick first shell

tool. These calculations are plotted as χ(k), |χ(R)|, and

Re[χ(R)].

As you can see, these two calculations are identical. You cannot even

see the blue trace underneath the red trace. It is clear that the QFS

calculation can be substituted for the more proper FEFF calculation of

the contribution from the nearest neighbor.

Why does this work?

FEFF starts by calculating neutral atoms then placing these

neutral atoms at the positions indicated by FEFF's input

data. Each neutral atom has an associated radius – the radius

within which the “cloud” of electrons has

the same charge as the nucleus of the atom. The neutral-atom radii are

fairly large. When placed at the positions in the FEFF input data,

these neutral-atom radii overlap significantly. This is a problem for

FEFF's calculation of the atomic potentials in the material

because it means that electrons in the overlapping regions cannot be

positively identified as belonging to a particular atom.

To address this situation, FEFF uses an algorithm called the

Mattheis prescription, which inscribes spheres in Wigner-Seitz cells, to reduce the radii of all atoms in the

material together until the reduced radii are just touching and never

overlapping. These smaller radii are called the muffin-tin radii. The

electron density within one muffin-tin radius is associated with the

atom at the center of that sphere. All of the electron density that

falls outside of the muffin-tin spheres is volumetrically averaged and

treated as interstitial electron density. All the details are

explained in J.J. Rehr and R.A. Albers, Rev. Mod. Phys., 72,

(2000) p. 621-654 (DOI: 10.1103/RevModPhys.72.621).

The scattering amplitude and phase shift is then computed from atoms

that have a specific size – the size of the muffin-tin spheres

– and with the electron density associated with those spheres.

The reason that the two calculations shown above are so similar is

because the muffin-tin radii of the Fe and S atoms are almost

identical. This should not be surprising. Either way of constructing

the muffin tins – using the proper FeS2 structure or using

the rock-salt structure – start with Fe and S atoms separated

by the same amount. The application of the algorithm for producing

muffin-tin sizes ends up with nearly identical values. As a result the

scattering amplitudes and phase shifts are nearly the same and the

resulting χ(k) functions are nearly the same.

(Mis)Using the quick first shell tool beyond the first shell

This is awesome! It would seem that we have a model independent way to

generate fitting standards for use in ARTEMIS. No more mucking around

with Atoms, no more looking up metalloprotein structures. Just use

QFS!

If you think that seems too good to be true – you get a gold star. It

most certainly is.

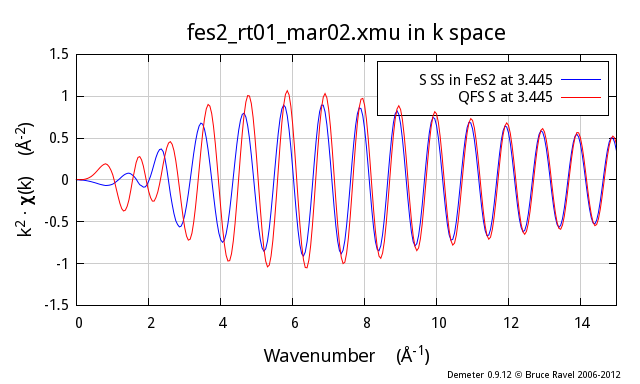

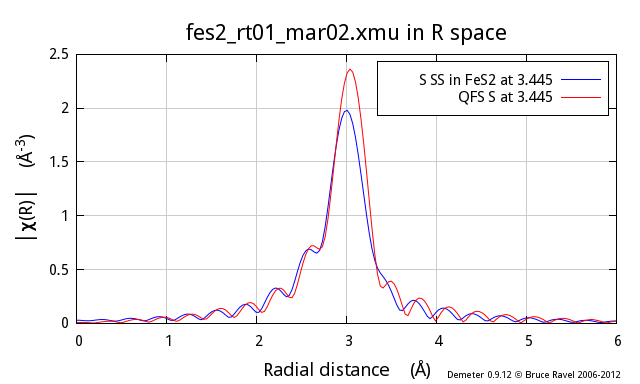

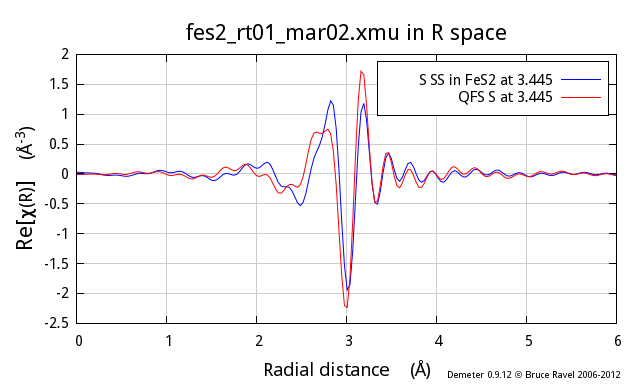

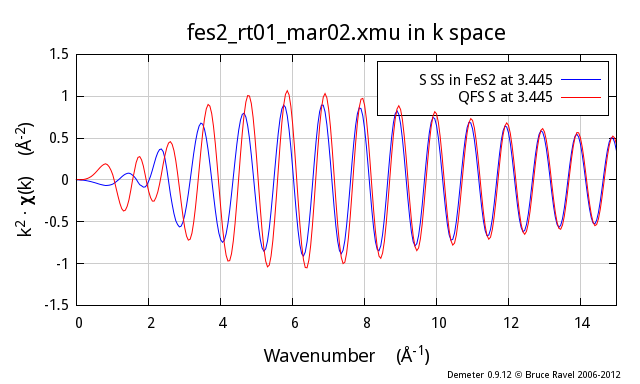

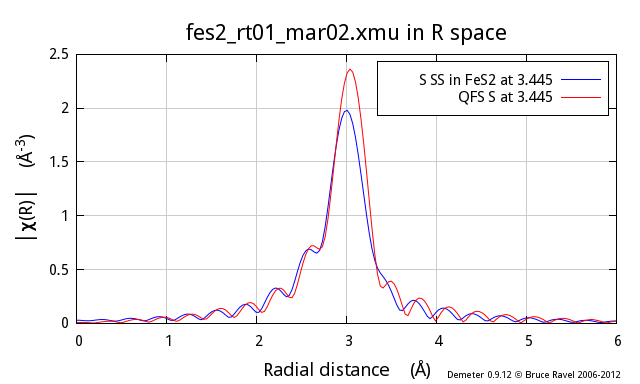

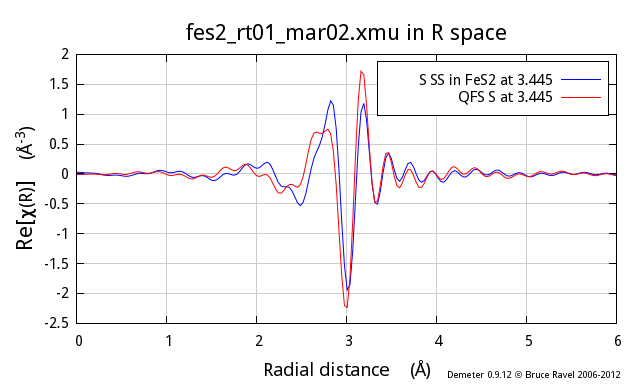

Following the example above, I now show the second neighbor from the

proper FeS2 calculation, which is also a S atom and which is at

3.445 Å. The red trace is a QFS path computed with a nominal

distance of 3.445 Å. As you can see, there are substantial

differences, particularly at low k, between the two.

So, why does this not work so well? In the proper calculation, the

size of the S muffin-tin has been determined in large part by the Fe-S

nearest neighbor distance. This same muffin-tin radius is used for all

the S atoms in the cluster. Thus, in the real calculation, the

contribution from the second neighbor S atom is determined using the same

well-constrained S muffin-tin radius as in the 1st shell calculation.

In contrast, the QFS calculation has been made with an unphysically

large Fe-S nearest neighbor distance. Remember, the QFS algorithm

works by putting the absorber and scatterer in a rock-salt crystal

with a lattice constant such that the nearest neighbor distance is

equal to the distance supplied by the user. In this case, that nearest

neighbor distance is 3.445 Å!

The algorithm for constructing the muffin tins requires that the

muffin-tin spheres touch. Supplied with a distance of 3.445 Å,

the muffin-tin radii are much too large, the electron density within

the muffin tins is much too small, and the scattering amplitude and

phase shift are calculated wrongly.

The central problem here is not that the red line is different from

the blue line – although that is certainly the case and it is

certainly a problem. The central problem is that, by misusing the QFS

tool in this way, you introduce a large systematic error into your

data analysis. This systematic error affects both amplitude and phase

(as you can clearly see in the figures above). What's worse, you

have no way of quantifying this systematic error. Your results for

coordination number, ΔR, and σ² will be wrong. And you

have no way of knowing by how much.

In short, if you misuse the QFS tool in this way, you cannot

possibly report a defensible analysis of your data.

In short, if you misuse the QFS tool in this way, you cannot

possibly report a defensible analysis of your data.

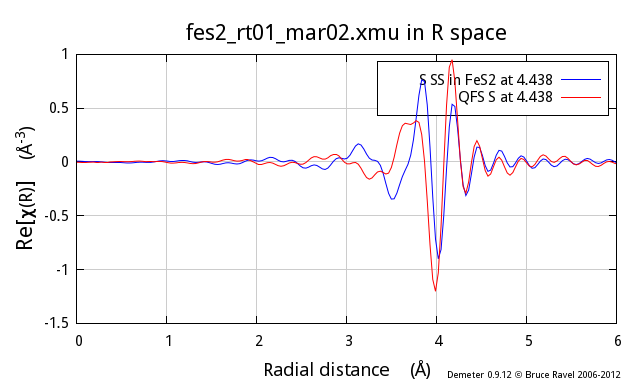

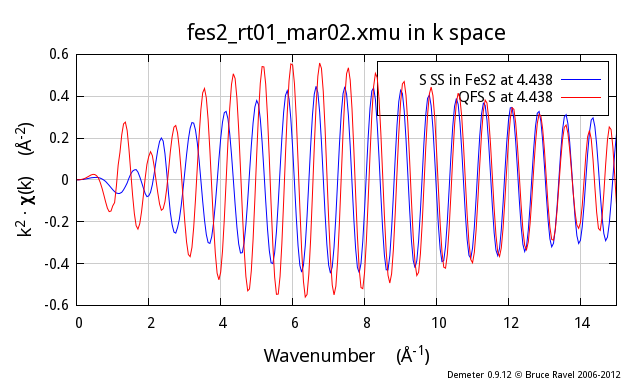

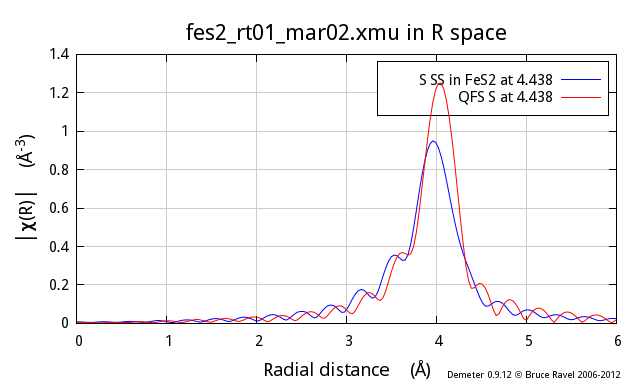

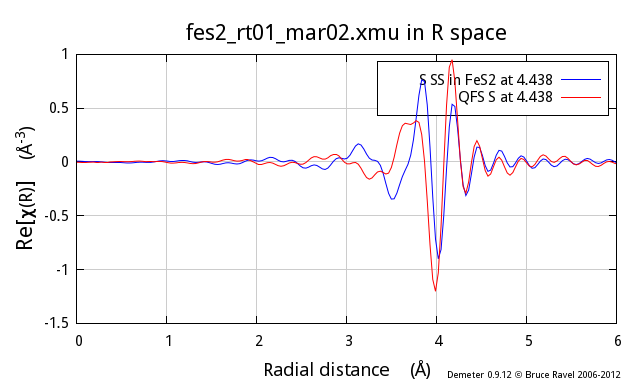

To add even more ill cheer to this discussion, the problem gets worse

and worse as the nominal distance of the QFS calculation gets

larger. Here I show the same comparison, this time for the fifth

coordination shell in FeS2, another S scatterer at 4.438 Å:

Executive summary

The quick first shell tool is given that name because it is only valid

for first shell analysis.

If you attempt to use the QFS tool at larger distances, you introduce

large systematic error into your data analysis. Don't do that!

So, what should you do?

Presumably, you have measured EXAFS on your sample because you because

you do not know its structure. The point of the EXAFS analysis is to

determine the structure. The upshot of this discussion would seem to

be that you need to know the structure in order to measure the

structure. That's a catch-22, right?

Not really. As I often say in my lectures during XAS training courses:

you never know nothing. It is rare that you cannot make an educated

guess about what your unknown material might resemble. With that

guess, you can run FEFF, parameterize your fitting model, and

determine the extent to which that guess is consistent with your data.

-

Crystalline analogs

-

In this

paper, Shelly Kelly demonstrates how to use FEFF calculations on

crystalline materials as the basis for interpreting the EXAFS of

uranyl ions adsorbed onto biomass. In that paper, she shows the pH

dependence of the fractionation of the uranyl ions among phosphoryl,

carboxyl, and hydroxyl binding sites. Obviously, there is no way to

make FEFF input data for uranyl ions on organic goo. However, Shelly

realized that the basic structure of the uranyl-phosphoryl or

uranyl-carboxyl ligands are very similar in the organic and inorganic

cases. Thus she ran FEFF on the inorganic structure and pulled out

those paths that describe the uranyl ion in its similar ligation

environment in the organic case.

The great advantage of using the inorganic structures is that the

muffin-tin radii are very likely to be computed well. The paths that

describe the uranyl ligation environment have thus been computed

reliably and with good muffin tin radii.

There is yet another advantage to this over attempting to use QFS for

higher shells – consideration of multiple scattering paths. In the

example from Shelly's paper, there are several small but

non-negligible MS paths to be considered for both carboxyl and

phosphoryl ligands. Neglecting those in favor of a

single-scattering-only model introduces further systematic uncertainty

into the determination of coordination number, ΔR, and

σ².

-

SSPaths

-

ARTEMIS offers another tool called an SSPath. An SSPath

is a way of using well-constructed muffin tins to compute a scattering

path that is not represented in the input structure provided for the

FEFF calculation. For example, suppose you run a FEFF calculation on

LaCoO3, a trigonal perovskite-like material with 6 oxygen

scatterers at 1.93 Å, 8 La scatterers at 3.28 Å or 3.34

Å, and 6 Co scatterers at 3.83 Å. Suppose you have some

reason to consider a Co scatterer at 3 Å. You can tell ARTEMIS

to compute that using the muffin-tin potentials from the LaCoO3

calculation, but with a Co scatterer at that distance, which is not

represented in the LaCoO3 structure. Unlike an attempt to use a

QFS Co path at that distance, the SSPath uses a scattering potential

with a properly calculated muffin tin.

The advantage of the SSPath is that it it results in

a much more accurate calculation than QFS. The disadvantage is that

it can only be calculated on a scattering element already present in

the FEFF calculation.

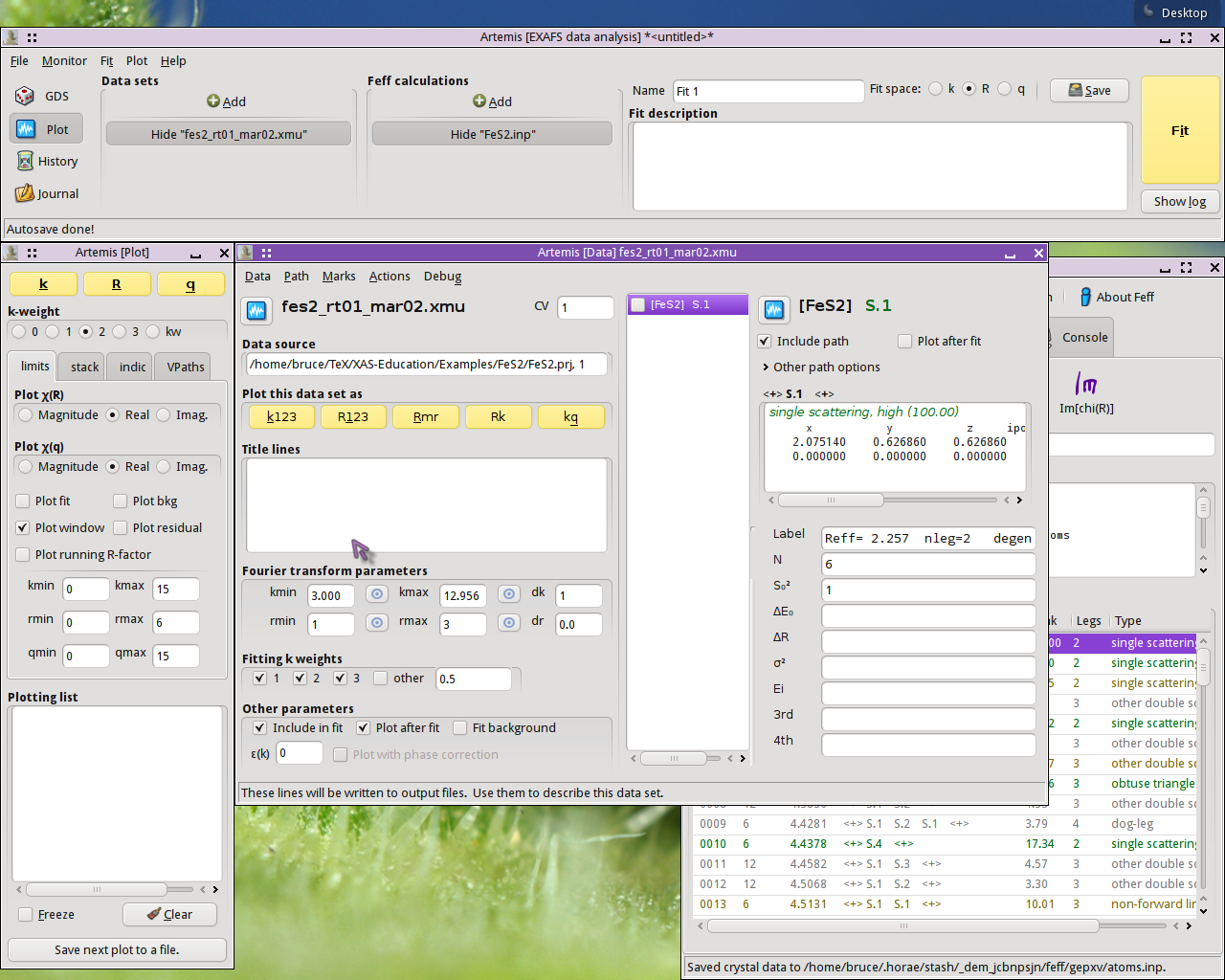

Reproducing the images above

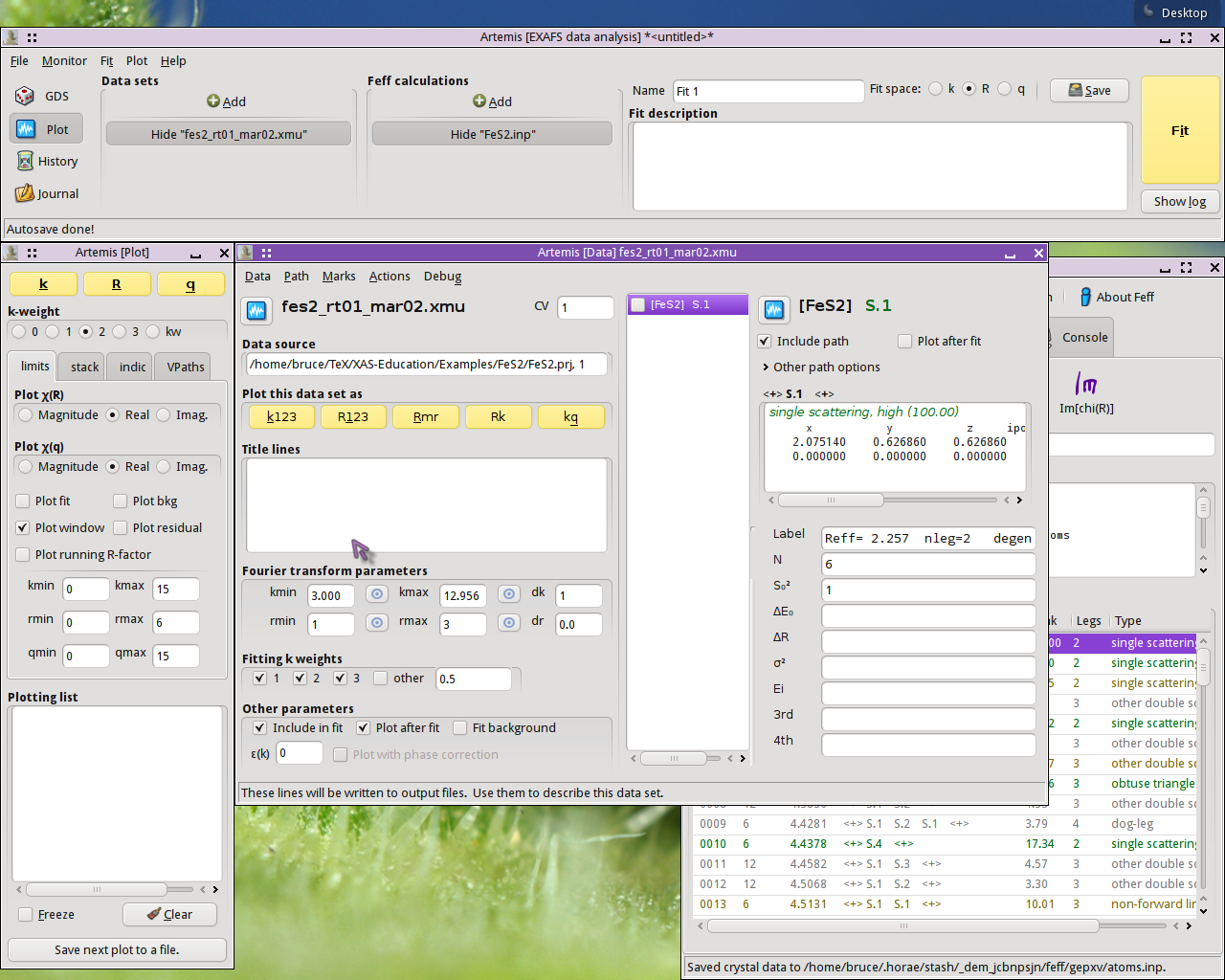

To start, I imported the FeS2 data and crystal structure into

ARTEMIS.

(You can find them here.)

I ran ATOMS, then FEFF. I then

dragged and dropped the nearest neighbor path onto the Data page. At

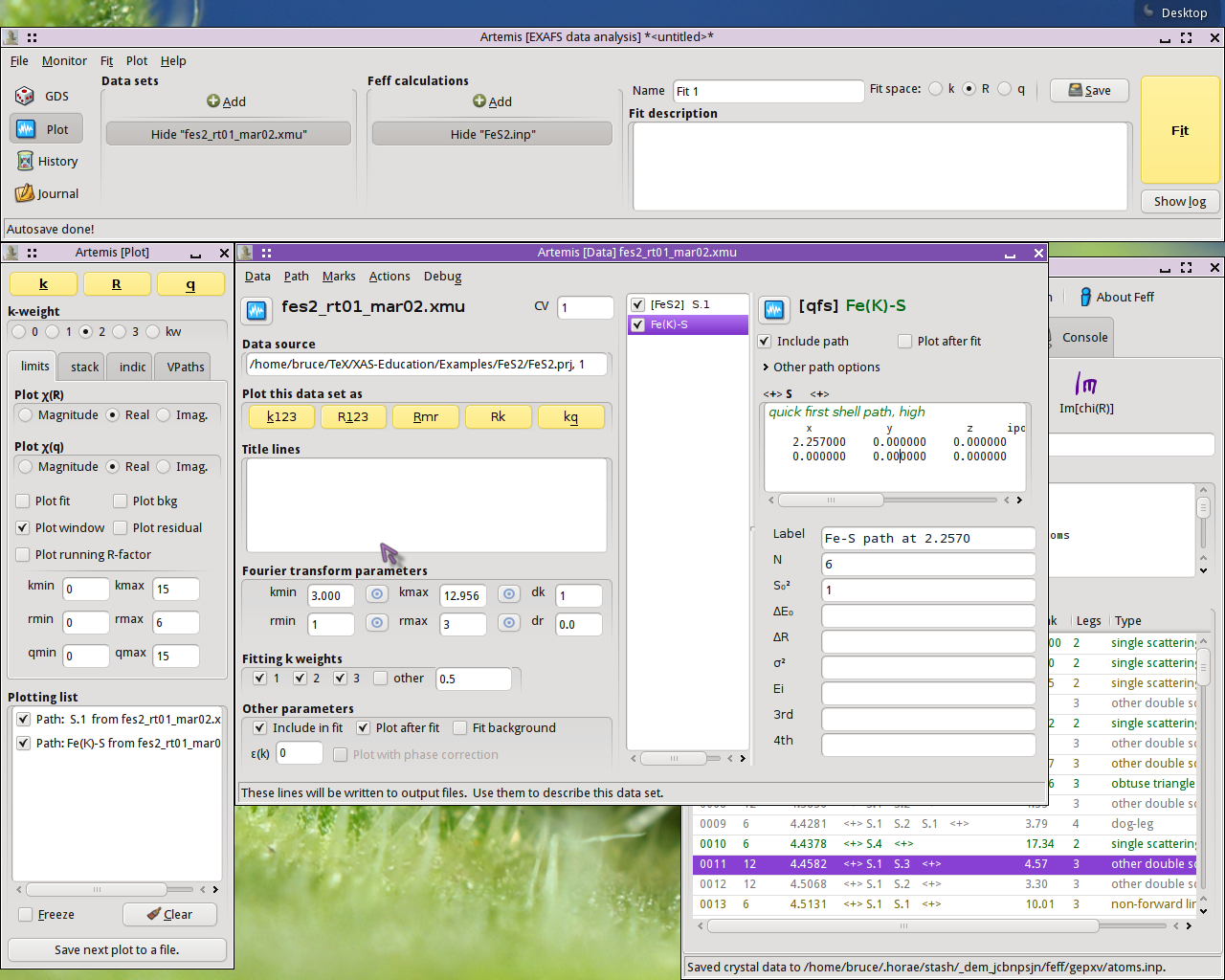

this stage, ARTEMIS looks like this:

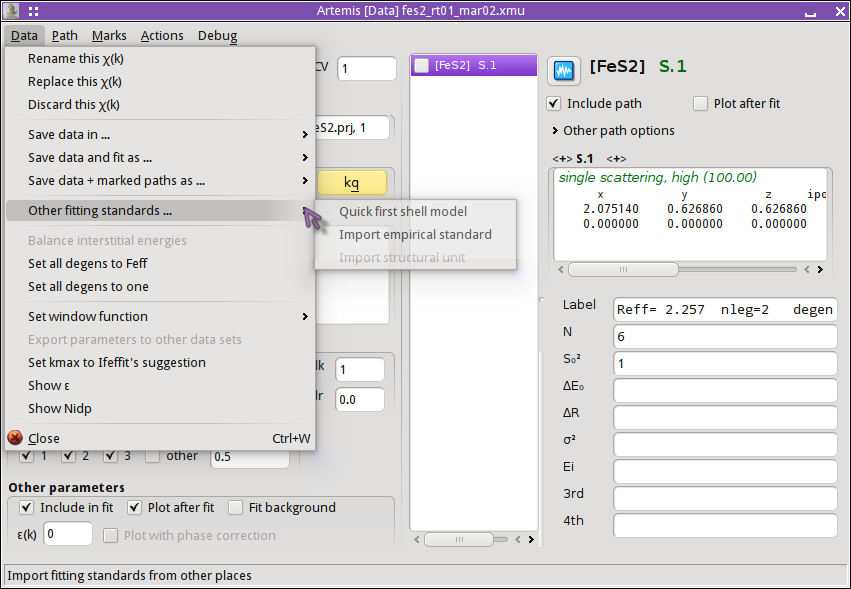

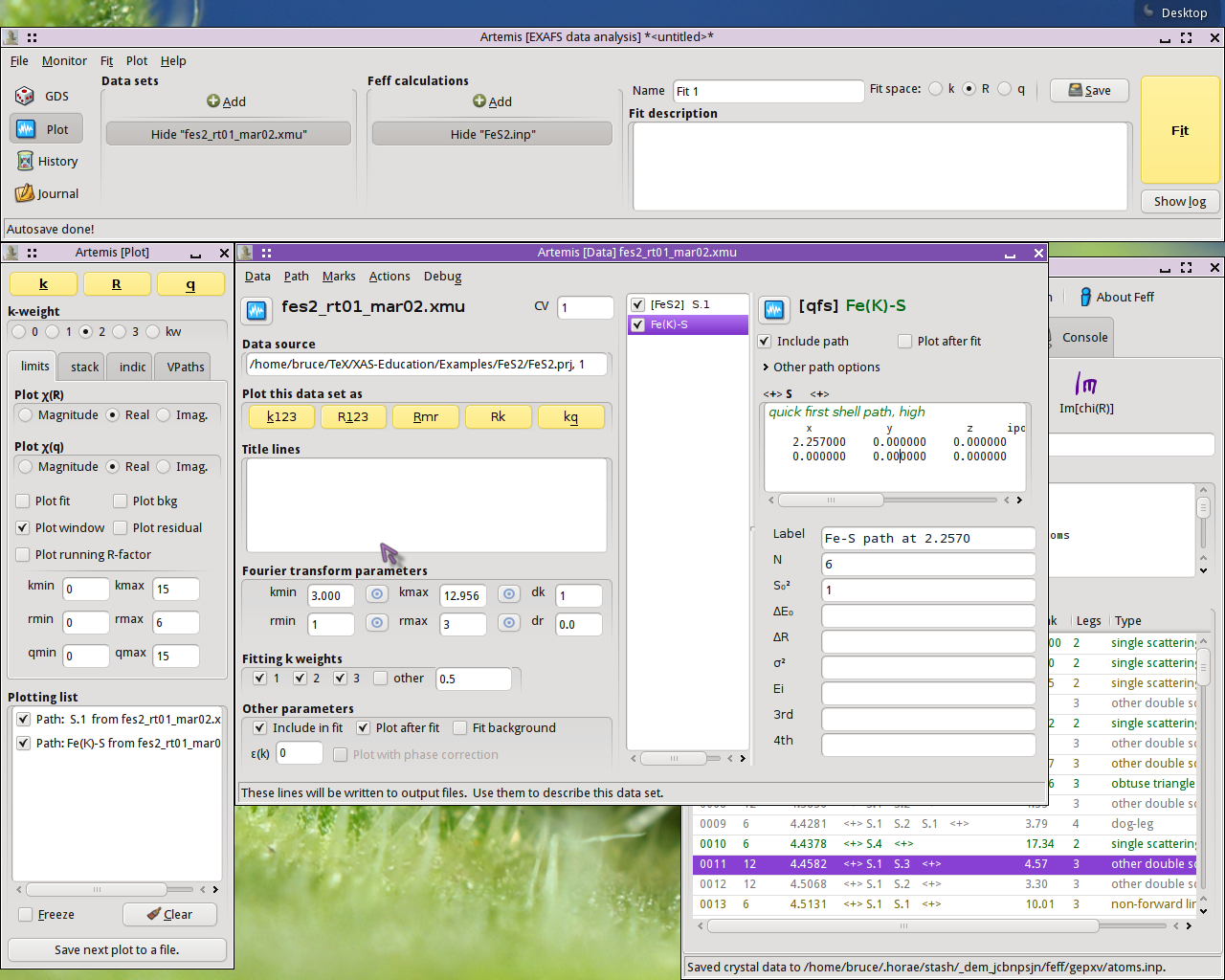

I begin a QFS calculation by selecting that option from the menu on the Data page:

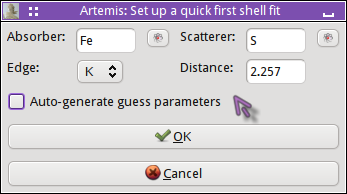

The nearest neighbor path in FeS2 is a S atom at 2.257 Å.

Clicking OK, the QFS path is generated. I set the degeneracy of the

QFS path to 6 so that I can directly compare the normally calculated

path (there are 6 nearest neighbor S atoms in FeS2) to the QFS

path. I mark both paths and transfer them to the plotting list. I am

now ready to compare these two calculations. To examine another

single scattering path, I drag and drop that path from the FEFF page

to the Data page and redo the QFS calculation at that distance.

![[Artemis logo]](../../images/Artemis_logo.jpg)

In short, if you misuse the QFS tool in this way, you cannot

possibly report a defensible analysis of your data.

In short, if you misuse the QFS tool in this way, you cannot

possibly report a defensible analysis of your data.